On Jane

From 2013

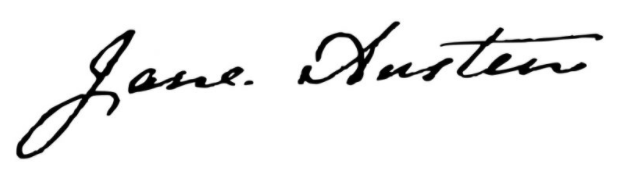

Jane Austen, the author of six of the wittiest, most enduring, socially astute novels of Western literature, was a quintessential bluestocking. It’s no wonder that Bas Bleu and its literary customers are among her biggest fans. And we’re not alone in our admiration. Jane Austen’s novels are among the most widely read and adapted books in print today, inspiring films, television shows, stage plays, book adaptations, even erotica. 2013 has been a particularly banner year for the author and her legion of fans, thanks to bicentennial celebrations of Pride and Prejudice’s publication.

(See pages 8-9 of our Fall 2013 catalog for our nod to the occasion.) Commemorations have included a P&P read-a-thon in Bath and a recreation of the Netherfield Ball. And in 2017, Jane will replace Charles Dickens on the Bank of England’s ten-pound note, only the third non-royal woman ever to grace the paper coin of the realm. (Oddly enough, this decision sparked controversy, some respectful, some downright hateful.)

It all began in 1775, in the English village of Steventon. The seventh of eight children born to George and Cassandra Austen, Jane was educated primarily at home by her clergyman father. She began writing at a young age, composing stories, plays, and poems to entertain her family. At fifteen, she penned The History of England, an amusing and precocious riff on popular schoolbooks of the time. Though Jane’s rural life was a sheltered one, she gained a broader view of the world thanks to her four brothers: two served with the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic Wars, one was a militiaman-turned-banker in London, and another was adopted by wealthy relatives. Their opportunities afforded their unmarried sisters Jane and Cassandra access to people and places they otherwise would not have encountered—and fodder for the novels Jane would create.

During her early twenties, Jane wrote Elinor and Marianne, which would become Sense and Sensibility, and First Impressions, the early incarnation of Pride and Prejudice. In 1787, First Impressions was rejected for publication, yet Jane continued to write, adding Susan (later Northanger Abbey) to her repertoire. In 1801, Jane and Cassandra moved to Bath with their parents, where they lived until George Austen’s death. By 1809, Jane’s wealthy brother Edward had settled his mother and sisters comfortably in Hampshire, sparking Jane’s productivity: Sense and Sensibility was published by “a Lady” in 1811, followed by Pride and Prejudice in 1813, Mansfield Park in 1814, and Emma in 1815. By 1816, Jane had completed Persuasion—and fallen prey to the illness (likely Addison’s Disease) that would claim her life in July 1817. She was just forty-one years old.

It wasn’t until the posthumous publication of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey in December 1817 that their author, Jane Austen, was acknowledged publicly as the writer of Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma. During her lifetime, Jane’s novels sold reasonably well yet garnered little critical attention. But as time passed and readers began to take a closer look at what was initially dismissed as light, comic fiction, there gradually dawned a greater respect for the novelist’s sharp wit and irony, her acute class and gender consciousness, and her deft grasp of human foibles.

Fifty years after her death, when British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli was asked if he read novels, he famously replied, “All six of them, every year.” After World War I, shell-shocked veterans were prescribed Jane’s novels to comfort their “tortured, troubled souls.” More recently, scholars have praised Jane Austen’s skill for creating characters who are still recognizable today—the tacky, socially ambitious Mrs. Bennet, the reserved-to-the-point-of-rudeness Darcy—and for writing about intelligent, savvy women. UCLA political science professor Michael Chwe goes one step further, finding evidence in Jane’s novels of a precocious proclivity for game theory, what the New York Times called “a strategic intelligence that would make Henry Kissinger blush.”

We could go on, but we won’t. At least, not about why we think Jane Austen was pretty much a genius. If you’ve read this far, we’re preaching to the choir. Instead, we’ll leave you with this excerpt from W.H. Auden’s 1937 poem “Letter to Lord Byron”:

She was not an unshockable blue-stocking;

If shades remain the characters they were,

No doubt she still considers you as shocking.

But tell Jane Austen, that is, if you dare,

How much her novels are beloved down here.

She wrote them for posterity, she said;

‘Twas rash, but by posterity she’s read.

You could not shock her more than she shocks me;

Beside her Joyce seems innocent as grass.

It makes me most uncomfortable to see

An English spinster of middle class

Describe the amorous effect of “brass”,

Reveal so frankly and with such sobriety

The economic basis of society.