On Edward Gorey

By now you’ve probably noticed that Edward Gorey’s name pops up frequently in the Bas Bleu catalog. We are, obviously, fans. But just in case your knowledge of the man is limited to the items you see in our pages, we thought we’d share a brief biography of the author/illustrator whose work was hailed by New Yorker literary critic Edmund Wilson as “equally amusing and sombre, nostalgic at the same time as claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned.”

Edward St. John Gorey was born in Chicago on February 22, 1925. An imaginative child who claimed to have “read Dracula at age 5, Frankenstein at age 7 and all of the works of Victor Hugo by age 8,” he began drawing at an early age. He credited his artistic tendencies to his great-grandmother Helen St. John Garvey, a greeting-card writer and artist whose work was popular during the nineteenth century. With the exception of a semester spent at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943, Gorey was largely—impressively—self-taught.

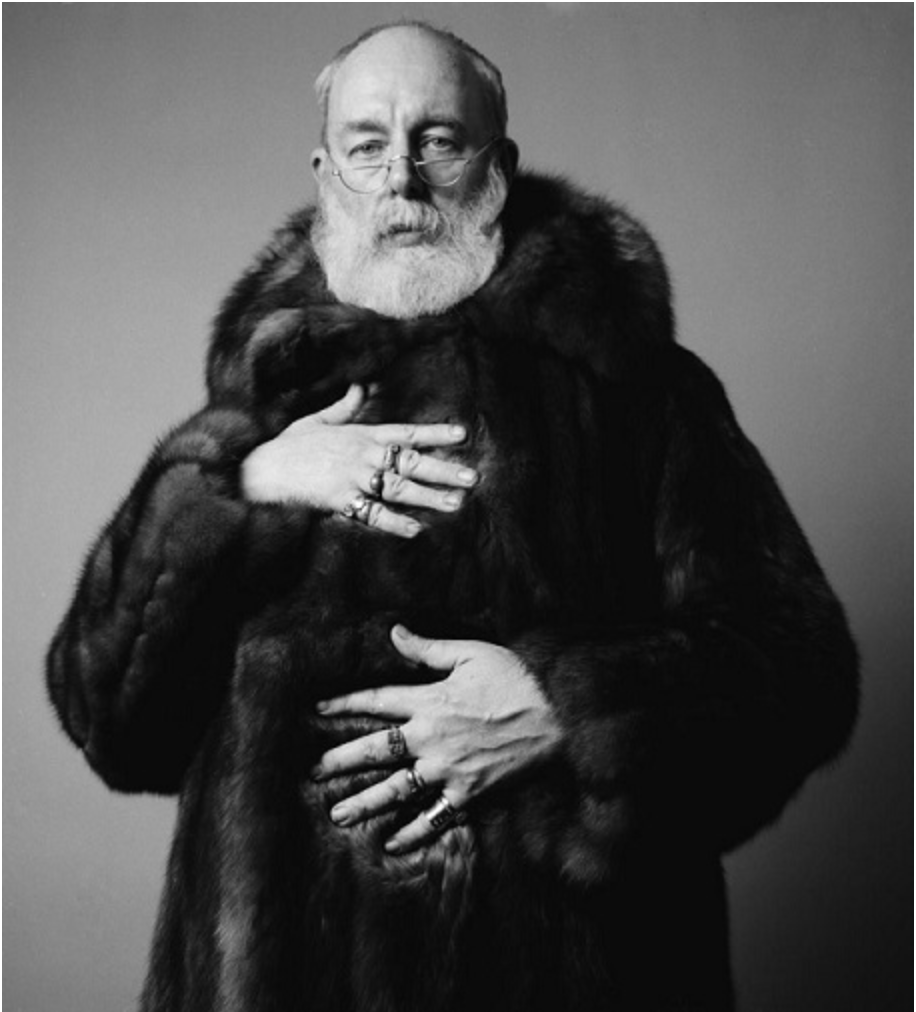

After a stint in the U.S. Army, Gorey headed to Harvard. He graduated in 1950 with a B.A. in French literature, but “wandered” professionally for several years, telling the Boston Globe in 1998: “I wanted to have my own bookstore until I worked in one. Then I thought I’d be a librarian until I met some crazy ones.” Eventually he landed a spot in the art department at Doubleday publishing, tasked with illustrating book covers and interiors for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, and T. S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. In his off-hours, Gorey toiled at his own creations, grim yet arch manuscripts illustrated with evocative pen-and-ink drawings. Though his work was initially dismissed as “ghoulish” by publishers, his first book, The Unstrung Harp, hit bookshelves in 1953, quietly launching the young man’s reputation for “whimsically grim storylines with dour yet dancerly protagonists.…Edwardian ladies, fur-coated gentlemen, ill-fated children, or unusual animals.”

Throughout his lifetime, Edward Gorey would publish more than ninety books, often under pseudonyms he took great delight in crafting: Ogdred Weary, Eduard Blutig, D. Awdrey-Gore, and Mrs. Regera Dowdy, just to name a few. He also illustrated dozens of titles by such literary luminaries as John Updike, Muriel Sparks, Edward Lear, Hilaire Belloc, and Charles Dickens. But his astonishing catalog of work isn’t limited to book publishing. Gorey designed souvenirs for the Metropolitan Opera and the New York City Ballet, whose choreographer George Balantine he regarded as an “artistic idol” and whose performances he attended faithfully for thirty years. In 1978, he won a Tony Award for his work as costume designer for the Broadway production of Dracula, and, since 1980, his work has been featured in the opening sequence of Masterpiece Mystery! on PBS. In a 1992 New Yorker profile, New York Review of Books co-founding editor Barbara Epstein classified Gorey’s illustrations as “beautiful, ravishing. He worked very slowly, with a tremendous perfectionism, and he would never let a drawing out of his hands if it was less than perfect.”

And yet the bald, bearded artist whose bestselling alphabet book The Gashlycrumb Tinies proposed twenty-six ways to dispatch with twenty-six children (“by awl, by brawl, by ennui”) was known by friends as a cheerful, witty, and engaging conversationalist who once admitted to Ron Miller, author of Mystery! A Celebration, “I’m very squeamish really.” He classified his fans as ranging “from dear little old ladies to rather distracted teenagers who sometimes turn up at the door.” He loved cats (he had six) and he disliked being called “macabre.” When Miller asked him, “What’s the biggest myth about your work?” Gorey replied, “That it’s gothic. Years and years ago, somebody wrote a very nice piece about me and referred to me as ‘American gothic.’ It sort of stuck.”

Yet how else to describe the man who penned such “menacing little books, written as if by moonlight”? Remembering his friend in The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, fellow author Alexander Theroux confided that Gorey “read every book possible. He had wide interests. There wasn’t a subject that didn’t interest him. I always said I wondered which Edward Gorey would show up on a given day. He was a film critic, he was interested in cooking. He was a man that would seem to be a bird of paradise, very ornate—but he could be a quiet and subdued and fairly shy person.”

Though generous with fans, Gorey brushed off his own celebrity, preferring to spend his time quietly living and working on Cape Cod, where he participated in community theater. As he explained to the Boston Globe, two years before his death in 2000, “When I think of other things that attain cult status, they strike me as somewhat feebleminded. I mean, I suppose it’s better being a cult object than nothing at all. But I don’t see how anyone has time to be really famous. I might get people dropping by who are slightly—unhinged.”

These days, reports the New York Times,Gorey’s “name increasingly serves as shorthand for a postmodern twist on the gothic that crosses irony, high camp and black comedy.” But he wasn’t too concerned with labels, according to Theroux: “‘Edward was one of the few people I ever knew who did exactly what he wanted,’ he says. ‘He went his own way.’”

We’re so glad he did.