Black History Month Highlight: Belle da Costa Greene

Belle da Costa Greene’s extraordinary career as the personal librarian to J. P. Morgan is fictionalized in Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray’s beautiful, comprehensive novel The Personal Librarian. Today, we’re taking a look at her accomplishments, both real and speculated.

Belle da Costa Greene was born Belle Marion Greener in 1879, to Genevieve Ida Fleet and Richard Theodore Greener. Her mother, a music teacher, belonged to a prominent Black family from DC, and her father was the first Black Harvard graduate (class of 1870), an attorney, professor, racial justice activist, and dean of the Howard University School of Law. Belle had four siblings: her older brother Russell, her older sisters Louise and Ethel, and her younger sister Theodora. The family was raised in DC, alongside Genevieve’s relatives, but they relocated to New York in the mid-1880s when Richard was offered a position with the Grand Monument Association.

Belle’s parents separated when she was seventeen. In their rapidly changing world, Genevieve and Richard had differing opinions on raising their children. Genevieve saw their race as a hurdle, and took advantage of their light skin: Once Richard moved out, she changed their surname from Greener to Green, her maiden name to Van Vliet to assume Dutch ancestry, and swapped her children’s middle names with da Costa in order to claim Portuguese ancestry, excusing their darker complexion. Throughout her career, Belle’s fabricated past threatened to reveal itself, and she struggled to keep her story straight between her family history, her age (which is also disputed), and her name.

Most of Richard Greener’s papers are believed to have been lost in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, so his own story has slipped through the cracks. Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray revitalized his character in The Personal Librarian, depending on the time period and Greener’s political career to drive his desires and motivations. They explain Genevieve’s attempts to pass as white as the ultimate reason for Richard’s departure. From page 19 of the novel, after Genevieve reported the family as white to the census:

“Reporting yourself and our children as white is like turning your back on your own people. Turning your back on yourself.” There was a long pause before he spoke again, but when he did, it was barely a whisper. “And turning your back on me, most of all.”

A sob escaped by mother’s lips. “The fight for equality is over, Richard. You lost it. We lost it fifteen years ago when the Supreme Court overturned the Civil Rights Act that would have given all black and colored people the equal rights we deserve. Yet you continue to think something is going to change for the better. But the time for hope is past; things are only going to get worse. There is only black and white— nothing in between— and they will always be separate, but never equal. Segregation will take care of that.”

Belle’s mother and siblings moved into a cramped two-bedroom apartment on the Upper West Side, surviving off Genevieve’s violin lessons and Louise and Ethel’s teaching salaries. Russell attended an engineering graduate program at Columbia University, while Belle lived and worked as a librarian at Princeton University. This is where she met Junius Spencer Morgan II, who introduced her to his uncle J. P. Morgan. In 1905, she began working as the famous financier’s personal librarian.

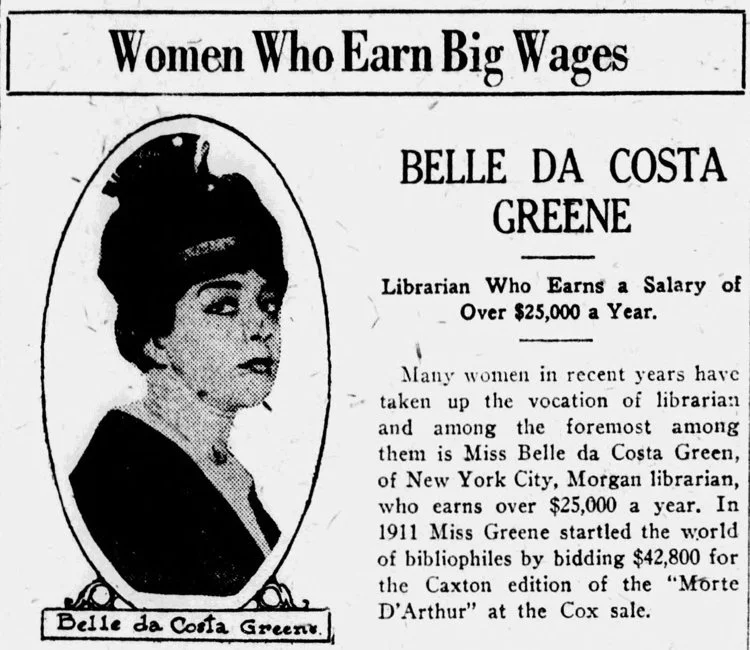

Belle da Costa Greene, courtesy of Theodore C. Marceau, from May 1911

On page 24 of The Personal Librarian, Belle meets J. P. Morgan for the first time.

Mr. Morgan rounds his desk, and I don’t speak as he pauses in front of me. He begins to circle me slowly, as if he’s assessing an expensive rococo painting…

“A real beauty.” Again, he speaks as if he’s appraising artwork, and I’m not sure if the known philanderer is considering me as a woman or inspecting me as a librarian. His comment does not invite a reply, so again, I say nothing. But then, he adds, “Da Costa. An unusual name.”

Repeating my practiced line, I say, “It’s my family name. My grandmother is Portuguese.”

…Then suddenly, he turns away. “I’ve heard what Junius thinks about these etchings, but I wonder about your view, Miss Greene. What do you think of acquiring the Vanderbilt Rembrandts?”

…I gather myself, draw from the extensive files in my mind. “Unlike his contemporaries, Rembrandt did all the work of the etchings for the prints himself— from incising the lines on the copper plate with various needles to submerging the plate in the necessary chemicals afterward. He thought etchings should be an important artistic medium, not simply an easy means to publicize his more expensive oil paintings, as most of his contemporaries did. From this perspective, Rembrandt’s etchings are masterworks by the genius himself, with a greater range of subjects than his more famous oil paintings.” I pause. “The etchings are remarkable. As the Pierpont Morgan Library will be, if I am placed in the position of librarian.”

Belle first organized, catalogued, and shelved Morgan’s extensive collection. By then, her knowledge, tactfulness, and desire to expand the library secured J. P. Morgan’s attention and trust, and he eventually allowed her to represent his interests abroad. She attended auctions, acquiring rare manuscripts, books, and art for the library. Most of the time, she was the only woman in the room, and she found ways to use this to her advantage.

She attended her first auction in 1906, chasing a 1638 copy of King Charles I’s Bible. To erase the doubts of the men there, she sat late, walking down the aisle with all eyes trained on her. She was a patient bidder, waiting to discern her competition before lifting her red scarf when the Bible’s price reached five thousand dollars, and winning it at fifteen thousand dollars.

J. P. Morgan gave her no limits at the auctions she attended. Often relying on her talent for catching men off guard, Belle achieved noteworthy success. Not only did she win the items she pursued, but she did it noticeably and with disarming charm. She was quickly elevated into the upper echelons of Gilded Age society. Though her name was printed in newspaper articles and gossip columns, she avoided interviews due to her fear of revealing her true identity. In a few years, Belle acquired “America’s greatest collection of incunabula and illuminated manuscripts,” and began seeking “the pinnacle of objects owned or created by rulers, royals, artists, and inventors in every category. Napoleon’s watch. Da Vinci’s notebook. Shakespeare’s folios. Catherine the Great’s snuffbox. George Washington’s letters” (from page 87 of The Personal Librarian).

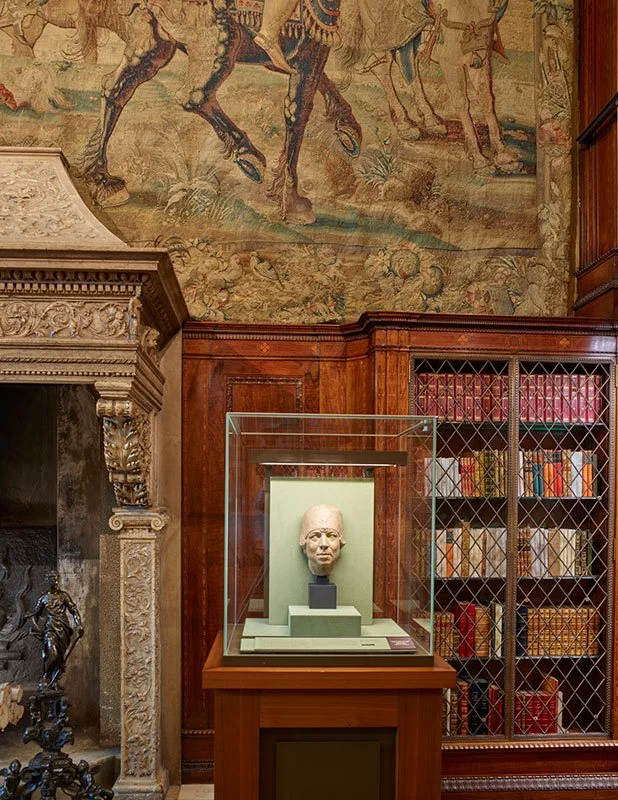

Inside the Morgan Library & Museum

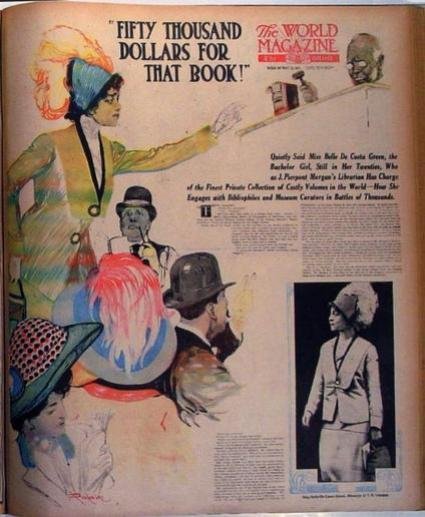

In 1911, Belle finally acquired the Caxton. J. P. Morgan’s white whale was printed in 1485 by famous printer and publisher William Caxton, a rare volume titled Le Morte Darthur by Thomas Mallory. Bidding against Henry Huntington, a California railroad tycoon, Belle elevated the price from fifteen thousand dollars to fifty. She was praised for rescuing the artifact from the wealthy collector, and perpetually exalted for making rare books accessible to the public.

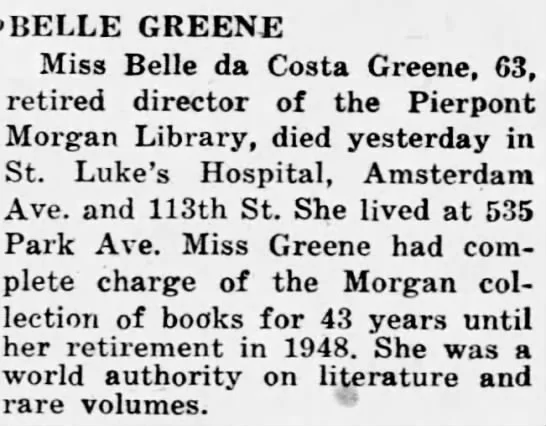

J. P. Morgan died in 1913, leaving fifty thousand dollars to Belle (approximately $1,300,00 in 2020 dollars). She continued to work as personal librarian to J. P. Morgan Jr., and in 1924, she was named director of the Pierpont Morgan Library when it became a public institution. She retired in 1948 and passed away in 1950, and was immortalized by the New York Times as “one of the best known librarians in the country.”

an article from a March 16, 1921 edition of the Omaha Daily Bee

an article from a May 21, 1911 edition of The World Magazine (New York)

Greene's death notice from a May 12, 1950 edition of the Daily News

the exterior of the Morgan library

a bust of Belle da Costa Greene remains in the Morgan Library

a portrait of Greene by French society artist Paul Cesar Helleu from 1913

Because Belle kept her private life so guarded (going so far as to destroy her personal correspondence before her death), much of her biography is extrapolated from known facts. In The Personal Librarian’s Historical Note, the authors wrote, “We also strove to capture as authentically as possible the historical context in which Belle lived: her upbringing, her career as the Morgan librarian and curator, her social life in the upper echelons of Gilded Age society, her dabbling on the fringes of the bohemian and suffragist worlds— and, most importantly, we tried to imagine and portray the sacrifices and strains of her passing as white in a racist society hostile to African Americans.”

Belle’s close personal and romantic relationships are mostly estimations. Throughout her career, rumors pervaded concerning her scandalous affair with J. P. Morgan, as their relationship certainly extended beyond professional. When asked about being his mistress, Belle is quoted as responding, “We tried!” The full extent of the affair (or lack thereof) remains unknown.

Her relationship with her father into her adulthood also prompts more questions than answers. There is no evidence of their connection after her parents’ separation, but there are reports of her taking a mysteriously timed trip to Chicago (unrelated to work), where her father was living at the time.

There is documented evidence of a romantic relationship between Belle and American art historian Bernard Berenson, which is played upon in The Personal Librarian. The intimate details are unknown, although some of her correspondence with him stood the test of time (he promised her he’d destroy them but did not). Some of those letters allude to her having aborted his child (Bernard was and remained married to his wife Mary, who was also an art historian), which seemed to affect Belle deeply.

Most importantly, Belle da Costa Greene is remembered as a woman who defied the societal odds stacked against her. In her own time, she was fierce and unapologetic, characteristics uncommon for a woman. Now that we know the truth of her ancestry, these characteristics are even more remarkable: Belle pursued rare historical artifacts for public accessibility despite the risk of her race being revealed, a consequence that certainly would have cost her her job, her social standing, and her carefully cultivated persona.

The Morgan Library & Museum has announced “a major exhibition devoted to the life and career of its inaugural director.” The Belle da Costa Greene Exhibition will open in Fall 2024.