7 Black Librarians You Should Know

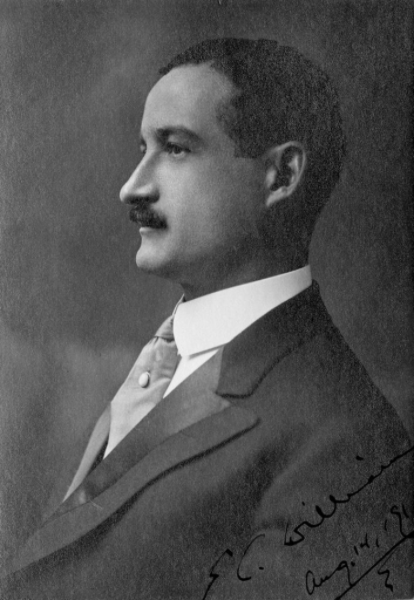

Edward C. Williams: Williams tops our (roughly chronological) list because he carries the distinction of being the first professionally trained African-American librarian in the United States. After graduating from Western Reserve University, he began a seventeen-year tenure at the university’s Hatch Library, where he was instrumental in expanding the library’s collection and establishing the WRU Library School. In 1916, he became head librarian at prestigious Howard University in Washington, DC, where he fought to improve the library’s resources and stressed the importance of employing professionally trained library personnel. He also taught several library and language courses (Williams was fluent in French, German, Italian, and Spanish), and he authored numerous poems, short stories, magazine articles, and books, including an epistolary novel about Washington’s black bourgeoisie.

Sadie Peterson Delaney: A trailblazer in the field of bibliotherapy (yes, that’s a real thing!), Delaney received her professional training at the New York Public Library, before joining the library’s staff at Harlem’s 135th Street Branch in the early 1920s. There, she expanded the library’s programs for children and used bibliotherapy to help young immigrants and troubled youths. To improve services for the visually impaired, she learned to read Braille and Moon Code (a writing system for the blind), and she advocated for developing a library collection focused on Black history and literature. In 1924, Delaney transferred her considerable skills to the VA hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, where she used bibliotherapy to revolutionize treatment for residents living with physical disabilities, mental illness, and emotional issues. During Delaney’s thirty-four-year career as the hospital’s chief librarian, librarians from around the world traveled to Tuskegee to study her innovative work.

Regina M. Anderson Andrews: Like Sadie Peterson Delaney, Anderson (later Andrews) worked at Harlem’s 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library. She was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, her apartment the site of regular salons and meetings attended by Langston Hughes and other influential Black writers, artists, and activists. Anderson helped W. E. B. DuBois found the Krigwa Players, a Black theater company, and wrote several of her own plays. In her library position, she organized art exhibitions and produced lecture and drama series (birth control activist Margaret Sanger and influential intellectual Hubert Harrison were guest speakers). After years of fighting for promotional opportunities for Black librarians, Anderson became the first African-American to lead an NYPL branch.

Charlemae Hill Rollins: In 1932, Rollins became children’s librarian at the George C. Hall Library, the first full-service branch of the Chicago Public Library built to serve the Black community on the city’s South Side. It was there Rollins made a name for herself as an advocate for “well-written children’s literature free of racial and ethnic distortions,” such as fake dialects and offensive or derogatory language and illustrations. During her career, she educated countless teachers, publishers, and fellow librarians about the importance of creating and disseminating children’s literature featuring African-America characters based on real life, instead of caricature or prejudicial views. Rollins retired in 1963 and turned her focus to writing; her published works include several biographies for young-adult readers.

Dorothy B. Porter: The first African-American woman to earn a library science degree from Columbia University’s library school, Porter joined Howard University’s library staff in 1930. She was hired to organize the library’s Moorland Foundation, a small collection of antislavery pamphlets and books. But over the course of her forty-year career, Porter transformed the collection into the expansive Moorland–Spingarn Research Center, a globally recognized repository for Black history and culture. Porter built a global network of contacts, developed new research tools and bibliographies—and rejected the limitations of the famed Dewey decimal classification system, which shelved books by or about black people under only two numbers: 325 (colonization) and 326 (slavery). Porter built on the work of her predecessors at Howard to create a more suitable classification system, organizing the collection to “highlight the foundational role of black people in all subject areas.”

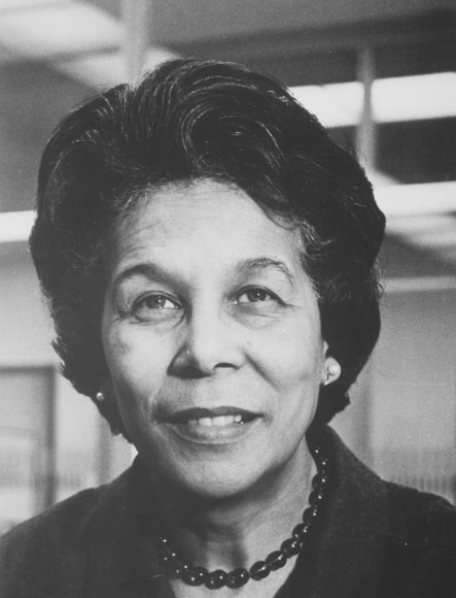

Clara Stanton Jones: Jones worked for the Detroit Public Library for twenty-six years before she was elected director in 1970, an appointment that spurred several of the library’s white board members to quit. As director, Jones launched a public-awareness initiative to encourage library use by inner-city residents, and spearheaded a movement to expand libraries “from simple book depositories into the information, resource and educational meccas they are today.” In 1976, she became first Black president of the American Library Association, and was instrumental in the ALA adopting a “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness” for staff and patrons.

Carla Hayden: Of course our national librarian earned a spot on our list! In 2017, Hayden became the first female and the first Black American to be named Librarian of Congress, supervising the world’s largest library. Like Charlemae Hill Rollins, Hayden worked as a children’s librarian for the Chicago Public Library early in her career, later serving as a museum librarian and a university professor. She was CEO of Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library in 2015, when protests broke out in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death. In the midst of the chaos, Hayden chose to keep the libraries open, even as many stores and businesses closed their doors. “The community protected the library…and we knew that they would look for that place of refuge and relief and opportunity.” In her national role, Hayden plans to use digitization to make the Library of Congress’s collection (162 million items!) more widely accessible, determined to do her part to “make information free for all.”